Special Situations: Flying with ACL Injuries

I’m going to give you a variety of tips and tricks gathered from various sources. First, the obvious… Every person and every injury is different. Your doctor / surgeon may have different protocols. If you’re already under their care, their advice has to come first. Though at the same time, they’re not always perfect. Take an active role in your care and ask questions. But anything said here is just a suggestion for ideas to look into, not official medical advice.

Damn. You had the vacation scheduled. Or you got hurt on vacation and now you want to come home. Or you’re post surgical and there’s a family thing you really feel you must get to.

Flying poses some special risks for those of us with fresh damage. There’s some things to watch out for post injury, but pre-surgery, and certainly post surgery. And some differences between flying short haul, (maybe a few hours), vs. those 10 hour plus international hops. I’ll try to cover most of the core issues.

Let’s start with this general tip: Do not be shy about asking for help! Most of us like to be independent. But now really isn’t the time. When there are assistive services available, use them. You might think, “oh I can make that distance.” But that will be the day something is extra messed up somewhere and you’re on your feet much longer than you anticipated. Use the help when you can get it so you’ll have the strength and stamina for the almost inevitable times you’ll need it.

Planning to Fly

Before going over the basics, let’s look at one of the most common questions… “How long after surgery until I can fly.” The practically useless, but true, answer is that planning to fly for post op isn’t all that possible for the first several weeks after. You certainly can plan. However the reality is none of us knows what we’re going to face. Regardless of surgery type, some people are weight bearing and getting around fine in days and in two weeks are off crutches and well into physical therapy. Others are close to bed-ridden for a couple of months or more. And others can get around with crutches or other aids, but are in non-trivial amounts of pain for several months and challenged with flexion. So planning is very challenging until you’re at least a week or two post op and you have some understanding of what your recovery is looking like. This can make things very hard to deal with when the rest of the world is still moving and has expectations of you being somewhere else on a certain date!

Driving instead isn’t always that much better of an option; though can work sometimes. If possible, there’s also the train. During less than peak hours, it’s often not terribly crowded and if you can get the handicapped seat, you should be able to keep your leg straight and maybe elevated, (on your bag or whatever), and might be the best way to travel.

Risks

DVT

This is probably the gravest issue. It’s the most rare. But since it could seriously hurt or kill you, it certainly bears mentioning. It’s challenging to bring it up since it’s so unlikely and this post isn’t intended to be about fear mongering. Nonetheless, this is a real thing and you need to consider it and discuss with your doctor.

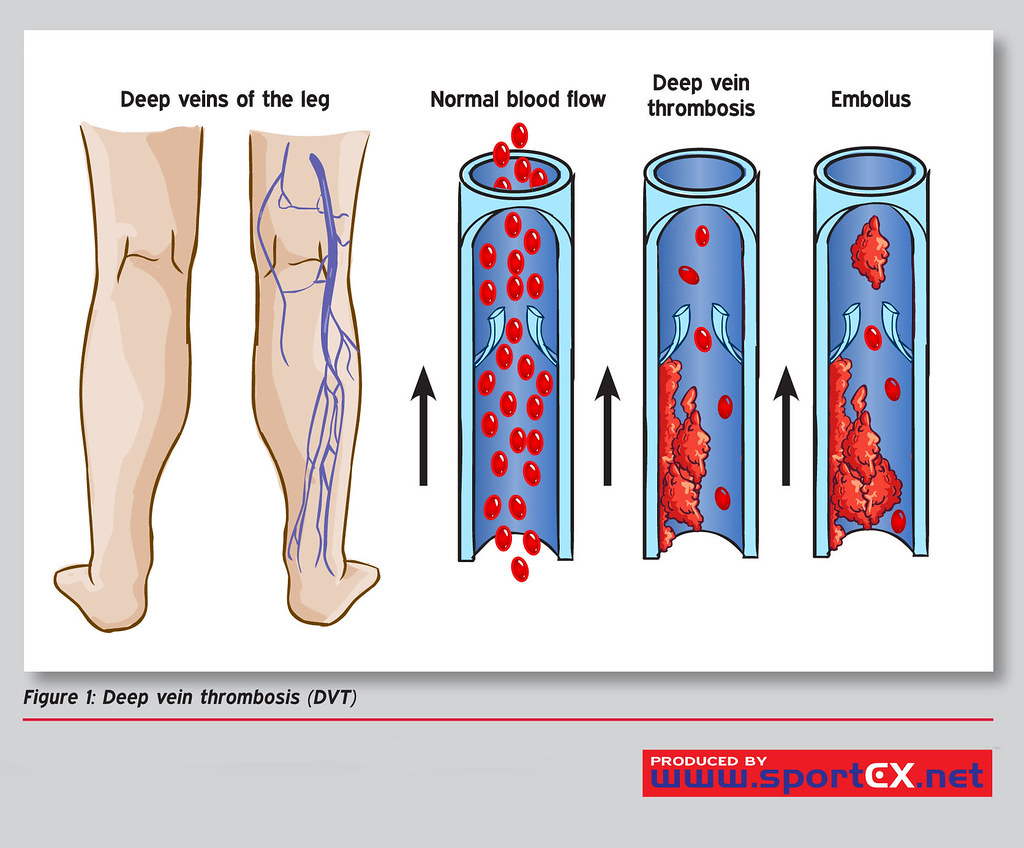

What is a DVT? A DVT (deep vein thrombosis) is a blood clot that forms in a deep vein, usually in the legs, often due to prolonged immobility during long flights. It can be dangerous if the clot travels to the lungs, causing a potentially life-threatening pulmonary embolism. If you fly pre-surgery, it’s maybe a lower risk than post-op, but one of the issues is lack of mobility. This reduces blood flow, which can help allow for DVT formation. Post surgery, you’re dealing with the surgical trauma itself, which outright activates the clotting system as part of a healing response. Meanwhile, some medications like opioids might further reduce movement and hydration, both of which elevate clot risk.

Also be aware that there’s higher DVT risk with obesity, smoking, and age 60+, longer flights (6+ hours) significantly increase DVT risk vs. short flights. Aspirin is sometimes recommended for DVT prevention in at-risk individuals, but should only be taken with a doctor’s approval, especially post-surgery.

One thing that’s interesting is that, anecdotally, some people have said their doctor’s said it was fine to fly a bunch of weeks after surgery. Different doctors have different protocols. Others may say it’s ok sooner, and prescribe a temporary blood thinner. It’s clearly something you need to discuss with your surgeon.

Swelling

Even though commercial planes are pressurized to 6-8,000 feet, that’s enough that at altitude you’ll probably get more swelling. And 2 hours might not be so long as to be a clot risk, that’s a thing, as discussed. Swelling can be painful and also restrict movement.

You can try compression socks and a compression sleeve which can help, but doesn’t necessarily solve this issue. Also, you can try doing ankle pumps and other light exercises.

As well, bring some kind of leg wrap that can work with typical ice, (not gel packs which you won’t be able to bring on board anyway; maybe leave them in carry on for later), and some plastic baggies. You can probably get some ice before even boarding and then get more on plane. Maybe try to get some before. It might not last long, but you can’t always depend on getting ice on board. While the flight attendants might be happy to help you, the one time you actually need ice might be the one flight where the announcement comes that, “Sorry, our service company was late today; no ice.” Note that there may be some ways to bring ice packs on board with a doctor’s note to get them through security. But this will likely be time-consuming and might not even work everywhere. Better off to have flexible options in the first place.

Injured, But No Surgery Yet

A lot of this applies to everyone; pre and post surgery. Everything depends on your degree of mobility and stamina.

Mobility

General / Planning

- Seat Selection: Take special consideration of your seat selection. You won’t be able to use an emergency row as you won’t be able to assist with emergency exit row duties.. A bulkhead row might offer you the most room, though these typically have no place for your carry on if that’s an issue for you. Also consider if you want an aisle, so you can stretch out on occasion, but maybe don’t choose the aisle side of your actual injury. Why? Because you may feel compelled to leave your leg out all the time. And that’s just begging for someone to slam into it. Or worse, get jammed up by a heavy service cart, which could do some serious damage. In any case, you may need to give up your crutches or cane for onboard storage. So if you need the bathroom, you’ll have to manage it on. your own or get flight attendant assistance to retrieve them. Alternatively, purchase a walking stick / cane that is collapsible to the point where it can fit in your carry on.

Are you flying with others? Make sure to be in the same row. The flight attendants might not like it and it might not work while the seatbelt sign is on, but if you’re on the window side you may be able to put your legs up on your traveling companions. You probably already owe them for all the other help they’re giving you, so what’s another, “I owe you big time for this one” thing? - Airplane Lavatory / Toilet: It’s tight in there. No way your leg stays straight. If you’re in a brace, this could be a challenge depending on what you need to do and if you need to sit or not.

- Flying in a Straight Brace: If your height is on the small side, maybe you can get away with this even in economy. Otherwise, this might just not work. And you’d better hope the person in front of you is friendly, or also talk to the flight attendant to make sure the person in front of you doesn’t slam their seat back because chances are your leg is extended as far as possible. You would be better off in at least Business Economy or ideally First Class though those can be prohibitively expensive. You can see if the airline will help you out, but be aware even if they were generous in your seat assignment, they can bump you when the time comes.

Getting to the Airport

Getting to the airport with an ACL injury requires extra planning to avoid unnecessary stress or pain. If you’re using crutches or a brace, arrange transportation that minimizes walking, such as a rideshare service or having a friend drop you off at the terminal entrance. Avoid parking in distant lots, as navigating shuttles or long walks can be exhausting and risky. Pre-arrange airport assistance through your airline; most offer wheelchair or cart services from check-in to the gate. If you’re driving yourself, check if the airport offers accessible parking close to the terminal, and give yourself extra time to account for slower movement through crowds or security. Inform the airline of your needs at least 48 hours in advance to ensure smooth coordination. And if you need accessible parking, you’ll need to have sorted out any permits or handicapped parking placards (that hang from rearview mirrors.)

Managing Your Bags

Managing luggage with an ACL injury, especially on crutches, can feel like an impossible task. Opt for a lightweight, rolling carry-on bag that you can maneuver with one hand, and avoid heavy checked bags if possible. If you’re on crutches, you quite likely won’t be able to manage baggage at all, even the roller bags. (Maybe a backpack, but you’ll have to be careful about both the weight and the balance.) If you’re traveling with others, delegate bag handling to them. For solo travelers, consider using airport porter services or curbside check-in to offload luggage early. Pack essentials like medications, a small collapsible ice pack and lightweight snacks in a small backpack that’s easy to carry while using crutches. If you need to keep crutches accessible, choose a carry-on with a side pocket to store a collapsible cane. Always double-check airline policies for mobility aids to avoid surprises.

Getting Around the Airport

If security isn’t that bad and the distance to the plane isn’t that bad, then just crutch it if you like. Anything questionable? Don’t tough it out. When you arrive, immediately ask for assistance. Get the cart, a wheelchair, whatever. Get whatever you need. It will make things easier though security and certainly getting to the gate. Just clearing security can be a varied experience. Some places will just send you around the scanner and check you more carefully. But others might require you to take off any brace and not use any walking device to go through. This may sound shocking, but it happens. And this will vary by airport / country, maybe the mood of the security personnel. If you’re showing up on the cart or wheelchair though, they’ll have to deal with you a bit differently. At least you’ll be able to sit while your brace and crutches / cane go through a check. If you’re flying out of an airport that’s a big ski resort destination, chances are they’re rather used to this treatment.

Make sure to let them know ahead of time if you need help for transfers as well. And it would be nice to tip the cart / wheelchair person $5 or something also; though customs vary by country.

Getting On the Plane

At typical large airports, you’ll obviously want to get to the gate early, and identify yourself as needing special assistance. You’ll get on early.

At smaller airports, or for some shorter haul terminal areas even at large airports, you may need to navigate some stairs in the airport to to get to certain gate areas. There may be elevators available; there should be. But even if these are available, you may need to find assistance to activate them. Then there’s the need to walk out on the ramp, (which is what the tarmac / concrete area is called for the airplanes), and then use some kind of air stair unit to get on board. You may face some weather issues here as well. Ideally not serious snow or ice, which at airports will ideally be cleared! But it could be raining and still slippery.

At such venues, there might still be a lift of sorts to get you to the plane. For this, you really should call ahead and check availability and let them know you would need this. (You might actually get hauled up via a catering truck as that might be the only lift around.)

Getting Off the Plane

Leaving the plane with an ACL injury requires just as much thought as boarding. Notify the flight crew before landing that you’ll need assistance, especially if you’re using a wheelchair or cart at the destination airport. Stay seated until most passengers have deplaned to avoid crowded aisles, which can be hazardous with crutches or limited mobility. If you’re at a smaller airport, be prepared for potential air stairs or ramps, which may be slippery or steep. Ask for a lift or crew assistance in advance. At the gate, request help with your carry-on and ensure any mobility aids stored during the flight are promptly returned. If you’ve arranged for a wheelchair or cart, confirm it’s waiting for you. Allow extra time for connections, as moving through a busy airport post-flight can be slow and tiring.

Small Planes

It’s a very bad idea to fly on smaller General Aviation (GA) planes with this kind of injury. There will be little help or service to get you on or off. The seats will be very cramped. These planes are not pressurized and while you’re not likely to be flying that high, you could easily end up at 9,000 – 12,000 feet. Now you’re at higher risk of DVT and swelling. And you’re likely going to a little airport with few services anyway. And right now, I’m talking about the commuter hopper type planes. Anything smaller? Forget it. (The author writing this post is a private pilot by the way, and knows there’s zero sensible way to fit someone with this kind of injury in these kinds of aircraft. So there will be no small plane adventure safari’s in your near future!)

Post Surgical Flying

Most of the main issues have been covered already in general. However, post-surgical flying adds layers of complexity due to healing tissues, increased risk of blood clots, and limited mobility. You may need to manage pain, swelling, and stiffness during the flight, and sitting for extended periods can be particularly uncomfortable. Always consult your surgeon before booking a flight, as they may recommend delaying travel, prescribe blood thinners, or suggest specific precautions like compression garments or frequent movement. If you must fly, aim for shorter flights, upgrade your seating if possible, and prioritize rest, hydration, and assistance throughout the journey. If you can afford to fly private, you’ll want to discuss your issues with the company providing service. If it’s a medical flight service, they will likely have clear protocols to share with you.

Stories from the Trenches

Here’s a link to a subreddit with a search for Flying within the ACL Subreddit.

Here’s what you will find, besides various bits of advice like here. Some people will say, “I flew that afternoon! No problems!!! They even let me fly the plane!” (OK, not quite that.) Others will tell you it’s been weeks or even months and they were in quite a bit of pain from swelling or position or whatever.

You have to make your own choices. Just be very aware there are real risks to pushing it. And not a lot of help on board an airline for anything truly, especially on long haul flights. This injury and recovery can be challenging. Be well and best of luck with recovery!

See Also:

📰 Web Articles

- Travelling After ACL Reconstruction Surgery

- Is It Safe to Fly After Having Surgery?

- Surgeries That May Impact Your Ability to Fly Commercially During Recovery

- Avoiding Blood Clotting Complications When Flying Before and After Surgery

- How to Avoid Blood Clots When Flying: Advice from a Vascular Surgeon

- Wearing Compression Socks While Flying: Benefits and Side Effects

- Compression Socks for Air Travel: Minimizing Swelling and Discomfort

- Wheelchair and Guided Assistance